Articles

Anti-diarrhoeal Tablets that cause Diarrhoea Are Protein Pump Inhibitors safe in the long term? Belching – A blessing or curse? Colonic hydrotherapy: The Toxic Tide Colonoscopy and colon cancer - Screening Chronic Constipation - A Physiological Approach Cyclical Vomiting: The missed diagnosis Dan Brown, The Lost Symbol and Gastroenterology Deteriorating Severe Ulcerative Colitis? Diarrhoea is never caused by irritable bowel syndrome Diet and IBD Extraordinarly unhelpful investigations Frozen Fritz – The Mythbuster Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Exercise Going where no-one has been before Guidelines in IBD: A conspiracy? Heartburn: A review Imaging the small bowel Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Back to Basics Is a test too far a step too far? Is it safe to stop aspirin after a bleed? Leeches and Probiotics Low dose aspirin and gastrointestinal bleeding Obesity: A Modern Plague: Other Therapy Obesity: A Modern Plague: Medical Therapy Occult Blood Testing - is faecal occult testing passe? Oesophageal Cancer incidence is rising Osmotic laxatives: Are they safe? Preventing colon cancer Probiotics - Are they really helpful? Reduced risk of colon cancer in ulcerative colitis Severe retrosternal chest pain Side effects and dangers associated with the treatment of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis The causes of nausea, vomiting and rumination The Dangers of Eating Away From Home The DNA Diet The human diet - lessons from nature The new step down therapy for IBD - Update The pathophysiology of the irritable bowel syndrome Therapy of inflammatory bowel disease has changed: When will we? There is more to heartburn than acid We are behind the curve in treating Crohn's Disease What controls the human gastrointestinal tract: The BRAIN or the GUT Why persecute the Helicobacter pylori?

Chronic Constipation - A Physiological Approach

Your answer to this loaded question has to depend entirely on your definition of the condition. Previous generations believed that a comfortable defecation once a week may be normal. Is this interpretation correct? The answer may be likened to your walking speed. At the annual kindergarten sports day race, is the winner more normal than tail end Charlie. Both outliers may be more than two standard deviations from the mean. Both could therefore be called abnormal. Certainly neither is average but is the average normal?

Stool frequency and consistency has a similar distribution. To look at normal distributions in various population groups serves little purpose except to say, most are average. It is therefore more productive, comparing stool frequency and consistency with bowel physiology as we understand it. Breastfed babies, children and some adults will defecate while eating and/or minutes thereafter. This response is viewed as being normal but unfortunately destroyed in most by our civilising potty training. Babies and toddlers will however continue to defecate after each meal. This is probably one of the reasons why so many hanker over their youth.

What is normal?

Based on the above physiology it appears that normal might be a stool before breakfast and a second before bed in the evening. Big meals produce big stools and fasting constipation. I will elaborate later.

If we prefer to follow conventional dogma then the wisdom of committees and various consensus groups have defined constipation as less than 3 stools a week. Many patients who are ignorant of this classification view themselves as constipated in spite of daily defaecation. The most commonly used definition is the Rome lll criteria (Table l). It is useful to review the criteria for the Irritable Bowel syndrome at the same time (Table 2). From these criteria it can be seen that making a clinical diagnosis may not always be straight forward (1).

These various criteria mean that a patient who has constant flatus in the late afternoon and passes a formed stool at 5PM on 5 days of the week is not constipated. These formalised definitions may be useful for comparing patients in studies but are quite useless in daily clinical practice. An alternative patient centric approach is needed.

At the simplest level the definition of normal might be the easy passage of stool not associated with unpleasant symptoms.

What is constipation?

Constipation is the passing of stood with difficulty and associated with the unpleasant symptoms of the passage of wind while doing ones daily functions, spontaneous abdominal cramps and cramps related to defaecation. Symptoms of the irritable bowel are bloating (which is incidentally not related to intestinal gas), feelings of incomplete evacuation and inappropriate calls to defaecation. Mucous on the stool appears in both these overlapping conditions(1).

The abnormal physiology of constipation is slow colonic transit and subsequently dehydrated stools. Before we examine these abnormalities we need to exclude secondary causes of constipation (Table 3):

The physiology of constipation

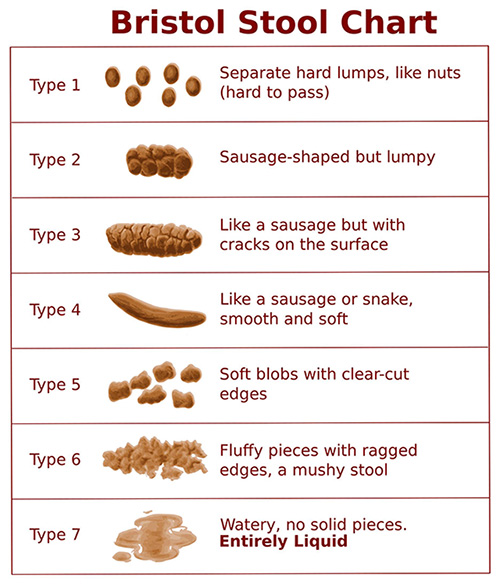

To have a normal bowel function enough stool needs to be made daily to have something to pass. As 95% of the stool volume consists of bacteria their numbers need to be increased to provide the ideal soft formed stool (see Bristol Stool Chart Type 4)(2). The only way to increase the number of bacteria in the colon is to feed them! This is the purpose of dietary fibre. The initial concept of fibre holding water such as in a gel is a small aspect of their function which is probably only useful when soluble fibre is given to patients without a colon to reduce the wateriness of their stools. In the normal situation the bacteria grow and thrive on the carbohydrate they find in the colon. Fibre is important but simpler carbohydrates also find their way in to the colon which together forms the fodder for faecal formation.

As the stool moves through the colon it changes from slurry in the caecum to the finished product in the sigmoid. During this process hydrogen, methane and short chain fatty acids are being produced by bacterial action. These gases are absorbed and metabolised by the colonic mucosa producing energy and multiple metabolic effects on lipid handling and indeed obesity. In humans who do not rely on colonic gas production for nutrition no gas should escape from the anus as opposed to the herbivores who exacerbate global warming.

Having increased stool size with dietary manipulations or the addition of fibre supplements there is still the option to use water holding chemicals such as polyethenol glycol, PEG (Kleanprep, Movicol and Pegicol). The advantage of PEG is that it will always produce a watery stool if enough of the agent is given. The disadvantage is the watery stool rather than the more normal bulky, Bristol Type 4 stool, produced by hordes of well-fed bacteria.

Now that we have produced adequate stool volume by bacterial proliferation in response to regular feeding with fibre, we need to address colonic motility to enable normal colonic transit.

Colonic transit time has an effect on stool consistency(3). Normal, a relative term, appears to be between 18 and 24 hours. This correlates with 1 or 2 stools a day.

Moderate exercise will also decrease colonic transit time. Emptying the rectosigmoid due to the physical stimulation of moving is well known and applies to horses, dogs and humans. More recently the beneficial effect of exercise on whole gut transit time has been documented(4).

One of the failures of motility studies is to define a simple picture of normal and constipated motility for patient education, diagnosis and treatment options. The pharmaceutical industry have marketed pro-kinetic agents over the years (Propulsid, Zelnorm) but side effects, usually cardiac, have led to their withdrawal. New agents being marketed are Procalopride (Resolor) and Lubiprostone (Amitixia). Both of these increase secretion and propulsive motility so should prove valuable additions to our options. Expense however may limit their general application.

In this regard we need to differentiate between above prokinetics which cause non-cramping propulsive movements with increased intestinal secretion and stimulatory laxatives such as prunes and Senna which cause mass peristalsis with a high pressure colonic lumen. Except as a last resort, stimulants should not be used as they tend to aggravate the irritable bowel component of constipation.

In addition to the pharmaceutical prokinetics, hard particles such a nuts, large seeds and mielie / corn kernels have been shown to decrease transit time(5,6). This they do without causing the spasms associated with stimulant fruits and laxatives. This mechanical prokinetic is not widely recognised or fully investigated. This is probably because then is little motivation to do so when society and the pharmaceutical industry is more interested in the chemical approach to even simple physiological problems.

The management of constipation?

So let’s get back to our constipated patient who passes one or less stools per day, passes flatus frequently and feels blocked up. The following steps are suggested.

STEP 1

Take a dietary history:

to determine the stool formation potential of the diet

For practical purposes bacterial food is carbohydrate. The most convenient is the fibre found in cereal products. For this purpose a simple table with common foodstuffs simplifies history taking (Table 4).

to determine the propulsive component of the diet

This consists of any 6

to identify stimulatory and non-stimulatory fruits eaten

The benefit of fibre in fruit is often outweighed by the stimulator effects of the fruit itself. (Table 5)

STEP 2

Re-design the diet

Increase the fibre in the diet to about 30 to 40 G a day to secure a soft bulky stool. Table 4 is a useful guide to a high fibre diet but in the end a cup of rough muesli and a cup of mielie / corn kernels give 27G of fibre daily ( 17 and 10 G respectively). This is usually sufficient to produce a normal soft stool. Initially the addition of this extra fibre inevitably leads to more gas production than the colon can absorb and therefore increases flatus and abdominal discomfort. To avoid this the transit time needs to be reduced.

Ensure enough natural pro-kinetic particles such as nuts, large seeds, pips and mielies/corn kernels are in the diet.

STEP 3

If there is no improvement in 3 to 5 days or previously 2 or less stools were passed a week extra help is usually needed.

PEG (Movicol) is useful if the diet cannot easly be manipulated (Retirement homes) but it tends to produce a watery rather than bulky stool. Children often do well.

Medicinal fibre supplements are useful temporarily. The soluble fibres such as lactulose tend to produce excessive flatus which is usually avoided by insoluble pysilium husk preparations.

STEP 4

If constipation remains a problem

New pro-kinetics, Resolor and Aximitia

STEP 5

Desperate circumstances may require desperate measures. This applies to very few patients

If laxatives are needed the slow acting senna based agents are more manageable than rapidly acting bisacodyl. Furthermore the fibre containing preparations such as Normacol Plus and Agiolax may ally our consciences.

STEP 6

Debunk some of the popular fallacies associated with bowel function.

Advising the drinking of more fluid is perhaps the commonest misconception. It has been shown stool consistency is affected by 5% dehydration. Normally this only occurs with vigorous exercise, long 12 hour aircraft trips and in the elderly. Generally drinking more fluid simply flushes the kidneys. This may be a good thing but certainly will not prevent constipation where the difference between a soft and hard stool may be less than 100cc(7).

Why do some patients not respond?

The main reason for failure is the underestimation of the irritable bowel component of the patient’s symptoms. A characteristic of irritable bowel is the disproportionate discomfort experienced as a result of rectosigmoid distension. Sometimes these patients land up in a vicious circle, increasing stimulatory laxatives which empty the colon but conversely increases sensitivity to small amount of residual stool. The presence of this is uncomfortable and results in strong feelings of incomplete evacuation and a desperate need to take further laxatives to clear the colon. Advice to increase stool volume and motility with the above advice is sometimes unacceptable. These patients have serious bowel function misconceptions and need intensive supportive therapy.

The concept of normal bowel function is misunderstood by a large percentage of the population and health providers. Unfortunately folklore makes more sense to many than the basic well researched physiology of the human digestive system. We need to move the population towards caring for their colonic function with adequate fibre and particles in the diet and away from the need for laxatives, excessive fluids, bowel washouts and the new panacea, probiotics.

References

Functional bowel disorders. Longstreth GF, Grant Thompson W, Chey WD Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480

Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Scand. J. Gastroenterol.1997 32: 920.

Gut 1996 Jul;39(1):109-13 How well does stool form reflect colonic transit? Degen LP, Phillips SF

Effect of moderate exercise on bowel habit. Oettle GJ. : Gut 1991 Aug;32(8):941-4

The intestinal effects of bran-like plastic particles: is the concept of 'roughage' valid after all? Lewis SJ, Heaton KW Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997:9;553

Roughage revisited: the effect on intestinal function of inert plastic particles of different sizes and shape. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW : Dig Dis Sci 1999 Apr;44(4):744-8

Mild dehydration . A risk factor of constipation. Arnaud MJ Eur J Clin Nut 2003:57;S88

TABLE 1

Rome lll criteria for constipation are:

Must include two or more of the following:

Straining during at least 25 percent of defecations

Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25 percent of defecations

Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25 percent of defecations

Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25 percent of defecations

Manual manoeuvres to facilitate at least 25 percent of defecations (eg, digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor)

Fewer than three defecations per week

Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives

There are insufficient criteria for IBS

Symptoms must be present for at least three months with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis.

TABLE 2

Rome lll criteria for IBS

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months associated with 2 or more of the following:

Improvement with defecation

Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

Symptoms must be present for at least three months with symptoms onset at least six months prior to diagnosis.

TABLE 3

Secondary causes of constipation

Effects of medication

Bowel obstruction due to cancer or strictures

Metabolic such as hypothyroidism

Neurological such as Parkinsonism

Psychiatric such as depression

TABLE 4

Fibre in Common Foodstuffs

White Bread

2.0 G / Slice

Brown and Rye Bread

3.0 G / Slice

Wholewheat Bread

3.4 G / Slice

Cornflakes

0.7 G / Half Cup

Weetbix

3.0 G / Biscuit

Meusli (average)

5.5 G / Half Cup

Formula 17 Meusli

8.8 G / Half Cup

Brown Rice

1.2 G / Half Cup Cooked

Potato – medium sized

1.1 G / Potato

Mielies / Corn

4.7 G / Half Cup

Green Peas

3.0 G / Half Cup

TABLE 5

Stimulatory Fruits

Apricots

Dried fruit mixtures

Figs

Peaches

Plums

Non-Stimulatory Fruits

Avocado pears

Bananas

Berries

Grapes

Mango

Melons

Note: Apples tend to constipate